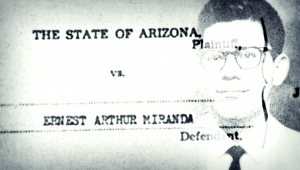

Dollree Mapp in Search and Seizure

Except in cases of probable cause, the police need a warrant to search your house without your consent in order for anything they find to be admissible in court. But that wasn’t always the case. In fact, until 1961, the police could barge right in and start searching. Anything they found was perfectly fine to use against you in court, warrant or no warrant. Sure, they were supposed to get one — but it wasn’t required. So why bother?

This changed because of one woman: Dollree Mapp. In 1957, a bomb went off in the home of Don King (yeah, that Don King). Cleveland police went to Mapp’s house looking for a suspect. When she refused to let them in without a warrant, they went in anyway. In addition to the suspect, police found a stash of pornographic material and Mapp was arrested and convicted on obscenity charges

Mapp appealed her conviction on the grounds that the search of her house without a warrant or probable cause violated her Fourth Amendment protection against “unreasonable searches and seizures.” On June 19, 1961 — 56 years ago today — the Supreme Court agreed. And in the landmark opinion in Mapp v. Ohio, Justice Tom Clark wrote, “Having once recognized that the right to privacy embodied in the Fourth Amendment is enforceable against the States, and that the right to be secure against rude invasions of privacy by state officers is, therefore, constitutional in origin, we can no longer permit that right to remain an empty promise.” Mapp’s conviction was thrown out.

Police were supposed to get a search warrant before Dollree Mapp. Because of her they need one.

Learn more about the case from Dollree Mapp herself in our film Search and Seizure. Dollree Mapp passed away in 2014.

On June 15, 1215, on a field outside London, a group of barons met with the King of England to sign what would become one of the most influential documents ever written, Magna Carta. King John, widely regarded as the

On June 15, 1215, on a field outside London, a group of barons met with the King of England to sign what would become one of the most influential documents ever written, Magna Carta. King John, widely regarded as the