About the Film

“You have the right to remain silent.” These words are now so familiar thanks to television shows and movies that it’s hard to conceive that they haven’t always been a part of American history. Before these words became a common staple of American culture the Fifth Amendment’s right against self-incrimination was virtually impossible to protect both in court and in police interrogation rooms around the country.

And then came Ernesto Miranda.

In 1963 Ernesto Miranda was arrested for robbery and sexual assault. Police investigators followed a trail of evidence quite literally to his front door and with the case that ensued the evolution of the Fifth Amendment began. Miranda was put in an interrogation room but was never advised of his right to not be compelled to incriminate himself, or of his Sixth Amendment right to a lawyer. Before long, he confessed. It is this confession that came into question during Miranda’s court trial. Did he voluntarily confess? Was he intimidated or coerced into confessing? Should he have had a lawyer at the time of his arrest in order to protect his Sixth Amendment right?

The Right to Remain Silent chronicles the legal, social and historical background that led to the Supreme Court’s 1966 Miranda decision, including the country’s history of police brutality and the legal controversies regarding the Court’s expansion of the Sixth Amendment right to counsel.

The jury convicted Ernesto Miranda within hours and he was sentenced to serve 20-30 years in prison. In 1966, Miranda wrote a handwritten petition for a writ of certiorari from prison – he asked the Supreme Court of the United States to hear his case. And it did.

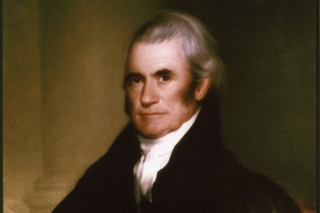

The Miranda opinion, written by Chief Justice Earl Warren, a former prosecutor and Attorney General of the state of California, is a testament to our country’s commitment to protecting criminal rights. Warren declares that police intimidation threatens human dignity, and that the best way to preserve it is not through the Fifth or Sixth Amendment rights alone, but through a marriage of the two: The Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination via the Sixth Amendment right to a lawyer to protect the privilege.

The Right to Remain Silent: Miranda v. Arizona is a story of how a man guilty of heinous crime influenced and ultimately improved the law and with it our constitutional rights.

Further Reading

The Miranda decision, via the NARA

The Supreme Court’s latest decision regarding Miranda rights, decided in summer of 2013

Earl Warren’s handwritten notes concerning the Miranda decision

Credits

Producer, Writer and Narrator, Robe Imbriano

Associate Producers, Gregory Blanc and Tiffany Hagger

Editor, Marc Tidalgo

Graphics Animators, Victoria Nece and Hiroaki Sasa

Photography, Edward Marritz

Production Associate, Stephanie Chang

Coordinating Producer, Heidi Christenson

Sound, Mark Mandler and Roger Phenix

Music, Gavin Allen and Ben Decter

Production Accountants, Mara Connolly and Andrea Yellen

Interns, Jennie Joyce and Kelin Long

Assistant to the Executive Producer, Jo Budzolowicz and Daphne Grayson

Senior Producer, Kayce Freed Jennings

Executive Producer, Tom Yellin